The Tennessee Valley Authority, the nation’s largest public utility company—as well as the sixth largest power provider in the United States—celebrates its 90th birthday this year. The organization had its origins in a hydroelectric dam constructed in 1916 on the Tennessee River at Muscle Shoals, Alabama. Its purpose at the time was to produce nitrates for use in explosives for the war effort, but once the war ended the future use of the facility remained unclear. The Coolidge administration sought to accept an offer from Henry Ford to sell the dam, as well as the rights to build a number of others, in the Tennessee Valley for the purpose of generating electricity to be sold to the residents of the region. However, a coalition of southern Democrats and Progressive Republicans in the Senate, led by Sen. George Norris of Nebraska, rejected it as a giveaway to big business. Norris instead proposed that the federal government operate the plant and provide electricity at low rates to the local population. Congress passed Norris’s initiative in 1930, but President Herbert Hoover vetoed the bill. “I am firmly opposed,” he wrote in his veto message, “to the Government entering into any business the major purpose of which is competition with our citizens.” The provision of electric power must be left in private hands, the president insisted, with the role of government limited to “the promotion of justice and equal opportunity.”

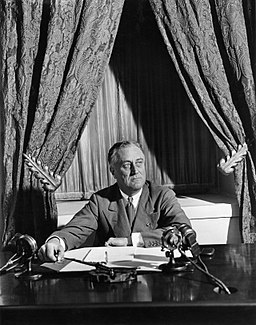

The fate of the Tennessee Valley was taken up by Franklin D. Roosevelt during the election of 1932. The people of that region were experiencing tremendous distress, even by the standards of the Great Depression. The river was prone to flooding, devastating much of the valley on a regular basis. Farming was the pillar of the local economy, and the global economic crisis had caused agricultural prices to plummet. Worse still, years of poor farming practices had depleted much of the soil, and when a severe drought came to the region in 1931, the result was widespread crop failure. At a time when average annual income was about $1,500, in the Tennessee Valley the figure was only $639.

After Roosevelt’s landslide victory in 1932, the new administration made the Tennessee Valley a top priority. Going even beyond what the Progressives had called for in the 1920s, Roosevelt called for a comprehensive program for the region, involving “flood control, soil erosion, reforestation, elimination from agricultural use of marginal lands, and distribution and diversification of industry.” Congress quickly approved, and the president signed the Tennessee Valley Authority Act into law on May 18, 1933.

The TVA brought a profound transformation to the region, which encompassed not only Tennessee but also parts of Kentucky, Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. Government agricultural experts came to the region to teach farmers about the latest techniques in farming. Unemployed people were hired and put to work on a variety of projects such as planting trees, carrying out land surveys, eradicating mosquitoes, providing health education, and even operating a public library system. Within a year the agency had some 9,000 employees; by 1937 there were 15,000. TVA jobs paid relatively high wages—by local standards, at least—and workers were guaranteed an eight-hour day and a forty-hour workweek, with time and a half for overtime. The Authority was also known for hiring African Americans, and while they tended to occupy fairly low-level positions, they were paid the same wages as whites with similar jobs.

The most dramatic change, however, came with the construction of dams along a 650-mile stretch of the Tennessee River. Construction on the first, Norris Dam (named for George Norris) in eastern Tennessee, began in October, 1933, and fourteen others would follow over the next eleven years. Moreover, because each of the dams required the flooding of large sections of lowlands, entire communities had to be moved. The TVA purchased land at fair market value, and assisted families in moving to nearby areas. Some 125,000 individuals were relocated, and many towns and villages would end up at the bottom of the lakes and reservoirs constructed. Nevertheless, the system of dams solved the chronic flooding which had plagued the region, and provided inexpensive electrical power to millions of people who lived there. The availability of electricity also attracted industry to Tennessee Valley, particularly in textiles.

Many conservatives regarded the TVA as an example of socialism, an unconstitutional exercise of federal authority that cost massive amounts of money and upended the local way of life. Stockholders of the Alabama Power Company filed a lawsuit in 1934, claiming that the federal government had no right to enter into the power industry in competition against private providers. In December, a federal judge found for the plaintiffs, but the Supreme Court overturned the decision in Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority (1936). In spite of the objections, the Authority was immensely popular in Tennessee and the other parts of the country it served, and was frequently cited as an example of how the government could bring about economic development. Indeed, in the postwar period it would serve as a model for modernization projects in the developing world. In a speech in 1965, for example, President Lyndon Johnson promised to do something even bigger than the TVA in Vietnam, if the North Vietnamese would agree to make peace.

Today the TVA remains the property of the federal government; nevertheless, it operates largely as a private firm, and is not funded through taxation. Electricity generated by TVA facilities—no longer only hydroelectric dams but coal-fired, natural-gas-fueled, and nuclear plants as well—reaches some ten million residents. It stands as one of the most ambitious enterprises of the New Deal, and at 90 years old, it is certainly among the longest enduring.

John Moser is professor of history and chair of both the Department of History and Political Science and the Master of Arts in American History and Government at Ashland University. He is the editor of Teaching American History’s CDC volume, The Great Depression and the New Deal and the author of the Concise History by the same name.