Two billion euros! This may be the cost of the series of climatic disasters that hit the country between mid-July and mid-September, as estimated by Moschos Korasidis, managing director of the National Union of Agricultural Cooperatives of Greece. Giorgos Stratakos, secretary general of the Greek ministry of agriculture, agrees: ‘It’s a global problem’.

Dadia (Evros), September 2023. A Canadair from the French Civil Protection team, on standby as part of the European mutual aid operation. Photo: Fabien Perrier

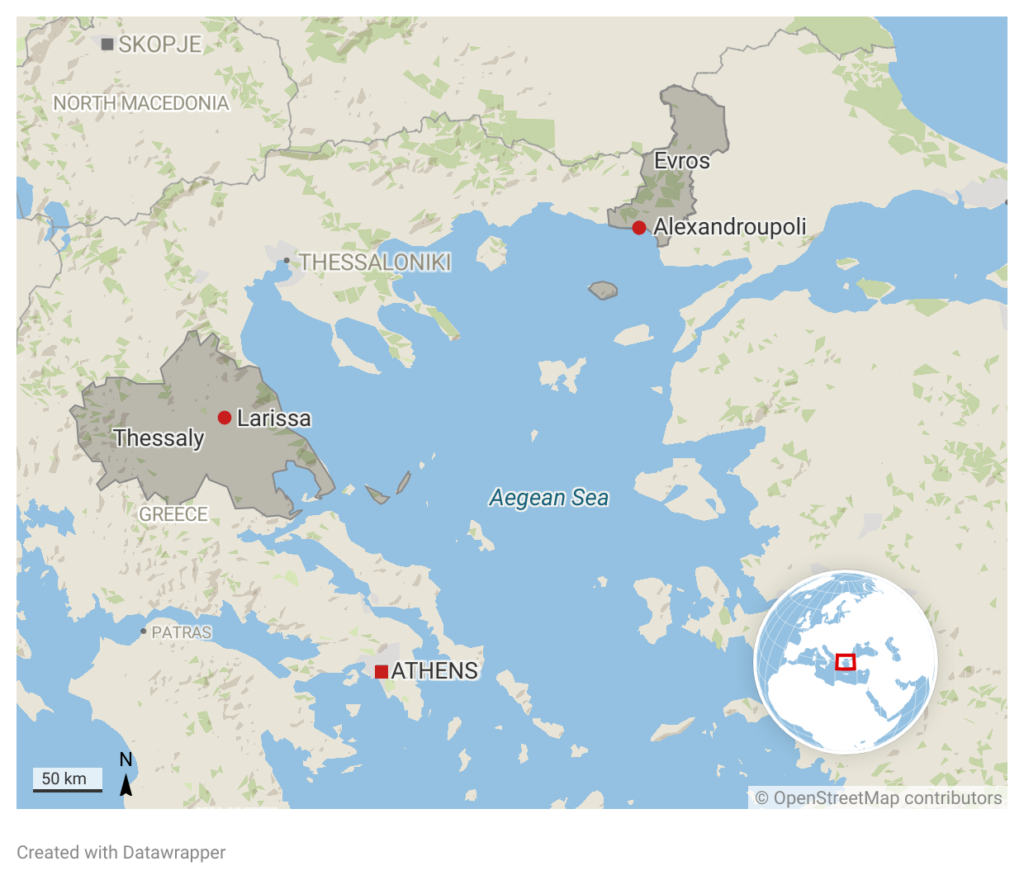

The fires first ravaged the area around Alexandroupoli, the main town in the agricultural region of Evros in the northeast of the country. They also swept through the islands of Rhodes and Corfu, and the area around Mount Parnes, the green lung near the capital Athens. Then the cyclones Daniel and Elias swept across the plain of Thessaly, the country’s food basket. After such devastation, what will recovery take?

This is the question on the mind of Kiriaki Chatzisavvas, 37. A biologist by training, she left the pharmaceutical industry to plant vines in Evros. ‘It used to be a little paradise here,’ she explains, pointing to the hillsides. ‘Now it’s a disaster.’ The vines are charred, the bunches of grapes withered, the ground strewn with ashes. The 7-hectare estate smells acrid. It will take her 5 to 10 years to get back to the same level of production.

This winegrower wonders whether she will be able to continue her practice based on ‘biodiversity’. She explains: ‘My approach was holistic, with little human intervention. I had even conducted an experiment with a beekeeper who had placed hives around the vines. Nature regained its balance.’ The fires that humans failed to control wiped out biodiversity, devastating vineyards, forests, farmland and olive groves.

Beekeepers are worried. Michalis, 31, had around 200 hives that he managed to save. ‘Honey production is my only source of income. Where are my bees going to feed when the fire has burnt everything?’

This is a major concern for Pavlos Georgiadis, an ethnobotanist from Evros who teaches at Hohenheim University in Germany: ‘The bees, which are essential for pollination, no longer have anything to eat even when the hives have been saved. In this situation, there is a risk of desertification. Fires have a huge impact on biodiversity! Thousands of olive trees have burnt down, arable land has been destroyed and animals have died in the flames.’ The researcher goes on: ‘Soil, air, water, biodiversity: everything is affected by these fires.’

In short, the entire ecosystem is at risk. ‘The biological health of the soil will be affected by floods and fires. It will be difficult to plant crops that are susceptible to soil-borne diseases because of the excessive moisture, as well as ‘root asphyxia’ due to prolonged flooding of the soil’, explains Moschos Korasidis. In his view, ‘this degradation of vast tracts of farmland poses a serious threat to local and national food security. Shortages of essential crops may lead to increased dependence on imports, with negative repercussions for the country’s balance of trade.’

Evros region, September 2023. Photo: Fabien Perrier

That warning may seem exaggerated, but the figures give an idea of the shortages and price rises that now haunt Greece. In Evros, fires burnt 94,000 hectares, almost half of them forests. 8,114 hectares of farmland were ravaged, 55.6% of the region’s total. Even centuries-old olive trees are in danger. Thessaly, which accounts for almost 15% of the country’s agricultural land (over 400,000 hectares), is a veritable agricultural reservoir and a wheat bread basket. Thessaly also produces 7% of the country’s sugar beet, 50% of its processed tomatoes and peas, 30% of its cotton and barley, 20% of the hay used in livestock farming, and a large proportion of its fruit and vegetables.

It is a mainstay of meat, milk and cheese production. Moschos Korasidis warns: ‘We also have disasters in stored products, such as cereals’. In his view, ‘between a considerably reduced supply of foodstuffs on the market and serious problems due to speculation, the conditions are ripe for price rises’. After ten years of economic and financial crisis, another crunch is looming, this time over food production.