On this date (June 25th) in 1929, President Herbert Hoover signed the Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928, authorizing construction by the federal government of a gigantic dam on the Colorado River, just west of the Grand Canyon. The dam, which would eventually be named after Hoover, took five years to complete, at a then unprecedented cost of $49 million (about $900 million today). When finished, it rose higher than any dam ever before built and enabled the construction of what was then the world’s largest power plant, as well as of the “All-American Canal,” which would carry water from the reservoir the dam created to California’s Central Valley. This allowed California to become a major producer of the fresh produce that now feeds the nation. Most interesting, the building of the Hoover Dam illustrates the unusual and problematic way water rights in the west are determined.

Why the Dam Was Built

Such a project had been recommended by the US Bureau of Reclamation as early as 1919. In the beginning, it was conceived primarily as a flood control measure, since periodic spring flooding on the Colorado had been known to inundate California farmlands as far as eighty miles distant from the river’s normal banks. By the time the Act was passed, the dam was also seen as a way of storing water for use in dry years and as a source of hydroelectric power for a rapidly growing population in the southwestern region of the country.

The act followed lengthy and difficult negotiations among the seven states that shared portions of the Colorado River Basin: the “upper basin” states of Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico; and the “lower basin” states of California, Nevada, and Arizona. (The division between upper and lower basins resulted from the topography of the Colorado River canyon, which was unusually steep, except at Lee’s Ferry, a point just upstream of the Grand Canyon, very near the border between Utah and Arizona. Only at Lee’s Ferry had those journeying southwest from Colorado been able to cross the Colorado River, so as to stake claims and settle in Arizona and New Mexico.)

A Compact Among Seven States

Herbert Hoover, Secretary of Commerce under Warren G. Harding, was appointed chair of the Colorado River Commission, which was charged with finding an equitable way of allocating the water resources among the seven states. Compacts between states were authorized by Article I, Section 10, clause 3 of the Constitution, which also specified that such compacts had to be approved by Congress. Never before had a compact been formed among so many states. Hoover would need to convince the delegates of each state to reach an agreement that would then be ratified by their state legislatures; then the agreement would have to be made official through an act of Congress.

Hoover had experience managing projects combining technical and political difficulties. After making a fortune as a mining engineer, he had organized an effort to provide food to occupied Belgium during the first world war. Later, he’d headed the American Relief Organization, which provided food to post-war Central and Eastern Europe. As chair of the new commission, Hoover spent six months in fruitless meetings, failing to persuade the state delegates to accept an equitable division of the water that would be stored behind the proposed dam. What finally persuaded the upper basin states to work out a compact with the lower basin states was a 1922 Supreme Court decision on a case involving a dispute between Colorado and Wyoming over use of the water in the Laramie River. To understand that decision, and to understand why seven western states needed to negotiate a compact to be sure to have the water they needed, one needs to understand how water rights in the west are granted.

First in Time, First in Right

Since the beginning of gold and silver mining operations in the western states, water rights had been claimed and held in a way that differed from the practice elsewhere in the country. In the east, those who owned land owned the right to draw enough water to irrigate their crops from rivers that crossed their land; frequent rains meant that there would usually be adequate water for those downriver. In the west, water was claimed as property independently of land. This happened because mining operations often used sluices to separate ore from the dirt or mud in which it was found, and the water needed to operate the sluices was often drawn from sources distant to the vein being mined. In time, a legal doctrine developed that gave the right to use any source of water to the first who claimed it, as long as that owner used the entire amount he claimed. If he used less in a given year, he could thereafter claim only the reduced amount.

Within western states, this practice of giving first rights to the first claimants helped to clarify who had a right to water in a region where dry conditions meant there was rarely enough for everyone who wanted it. It remained to be resolved what would happen if two states disputed the right to draw water from a river that ran through both. The Supreme Court declared in 1922 that in interstate disputes, also, the right to first draw water from a river was held by the first claimants. Since California had been settled prior to the southwestern states, this meant that California had a stronger claim on Colorado River water than the other states through which the Colorado flowed. The Court’s decision persuaded those states to cooperate with the Colorado River Commission, since they were more likely to get the water they needed through a negotiated process than through a judicial one.

Hoover summoned the delegates to the Colorado River Commission to a meeting at Bishop’s Lodge, a ranch in New Mexico accessible from Santa Fe only via several hours of driving on bad roads. He wanted to shield the delegates from the denunciations they’d receive at home if the concessions they made were reported. This strategy worked. The US Geological survey had estimated the annual flow of water through the Colorado River at 16.5 million acre-feet (MAF). The commissioners agreed to allocate 7.5 MAF to the upper basin states and 7.5 MAF to the lower basin states, leaving 1.5 MAF to be left to flow into Mexico. The agreement depended on California’s pledge to claim only the amount of water it was already drawing, 4.4 MAF. The compact was later ratified by six of the seven states concerned, Arizona being the lone hold-out. After the commission agreed to overlook Arizona’s refusal of the compact, Congress drafted the law that authorized building of the dam.

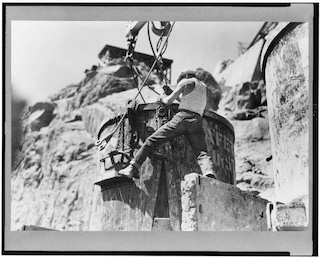

Constructing the Dam

The Bureau of Reclamation supervised the construction, which occurred between 1931 and 1936. More than 100 of the thousands who worked on the project died on the job. The finished structure was named the Boulder Dam by the Roosevelt administration, although in 1947 an act of Congress renamed it the Hoover Dam.

A concrete gravity-arch structure that is 726.4 feet tall and 1244 feet long, the dam was built to hold over 28 MAF in the reservoir, Lake Mead, that it created. Today it holds less than 16 MAF. It turns out that the US Geological Survey greatly overestimated the annual water flow of the Colorado, having based its estimate on several years in the early twentieth century when rain and snowfall were heavier than at any time since the 1400s (tree ring analyses have helped to establish precipitation in centuries before records were kept). In recent years, water drawn from the reservoir has included water stored in prior years, and the level of Lake Mead is dropping.

Although the Hoover Dam remains the largest dam in the US, there are now fourteen other large dams on the Colorado River, including the Glen Canyon dam, located at Lee’s Ferry. Each captures water and generates hydroelectric power for the growing demands of towns and cities along the river’s route. The river is drawn from so heavily that it peters out in the Sonoran Desert several miles short of what was once its mouth in the Sea of Cortez.

For Further Reading:

Martin Doyle, The Source: How Rivers Made America and America Remade Its Rivers. Blackstone Publishing, 2021.

David Owen, Where the Water Goes : Life and Death Along the Colorado River. Riverhead Books, Reprint edition, 2018.

Marc Reisner, Cadillac Desert: The American West and Its Disappearing Water, Penguin: Revised Edition, 1993.