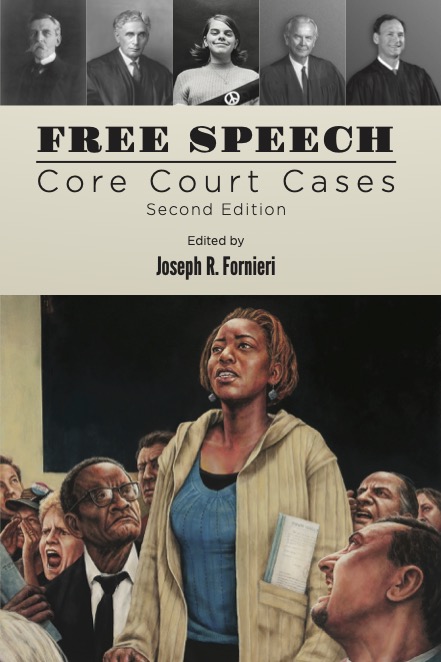

Teaching American History is excited to announce the release of our latest core document volume, the second edition of Free Speech. Edited by Joseph Fornieri, this reader contains a collection of twenty-six landmark court cases, an introductory essay, case introductions, a thematic table of contents, study questions, glossary, and suggestions for further reading. Take a peek inside the volume below!

Volume Introduction

While the language of the First Amendment seems straightforward, its text conceals as much as it reveals. Although “Congress” alone is mentioned, the First Amendment applies to any agent of the national government, including the president. As originally framed, the Bill of Rights guaranteed immunity only from the actions of the federal government, not the states. This changed in the twentieth century with the “doctrine of selective incorporation,” which applied the First Amendment to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause . . . The incorporation doctrine authorized the Supreme Court for the first time in its history to review state laws that potentially infringed upon the First Amendment. Moreover, the liberty guaranteed by the First Amendment should be understood primarily in terms of protection from government control. Thus, it may come as a surprise to some that the First Amendment does not apply to private institutions—those social, political, civil, and religious groups, associations, and corporations that are not units of the federal or state governments. So, while a state university is bound by the First Amendment, a private college or a religious association may restrict free speech or religious exercise as it sees fit, in accordance with its own mission statement.

With regard to free speech, a literal reading of the word “speech” is likewise misleading, since the Supreme Court has gradually extended the First Amendment’s free speech protections to include symbolic, nonverbal expression such as flag-burning, visual imagery such as pornography, commercial communication such as advertising, and children’s entertainment such as video games. Finally, although the First Amendment says “no law,” the right to free speech is not absolute. As Justice Holmes famously said, it does not give one the right “to falsely shout fire in a crowded theater.” Indeed, one of the enduring issues faced by the Supreme Court has been where to draw the line between protected speech and punishable speech. The goal of this documentary volume of landmark cases is to provide students with the basic texts and tools for understanding the Supreme Court’s evolving jurisprudence on freedom of expression. . . .

In conclusion, while these landmark cases contain many pearls of wisdom about free speech, history teaches us that we cannot always rely on the Court to safeguard our liberties. The Court’s decisions may be sidestepped or ignored. The Bill of Rights is only a parchment barrier unless sustained by habits of heart and mind that give it life. Some of the more recent challenges to the First Amendment have involved the control of media platforms, hate speech, cancel culture, political-corporate collusion, foreign disinformation, and campus protests, as well as debates over curriculum, broad antidiscrimination laws, and speech compelled by public and private bureaucracies. Wherever one stands on these controversial issues, free speech can only be preserved through a “First Amendment culture” that understands, cherishes, and jealously guards its preferred place in our democracy. This volume hopes to contribute in some small way to that worthy cause.

Sample Documents

Study Questions

25. Morse v. Frederick (2007)

A. Do you think Frederick’s message on the banner was entitled to First Amendment protection? What are the conflicting interests in this case? How did the school setting influence the Court’s reasoning in this case? To what extent did Frederick’s pro-drug message influence Chief Justice Roberts’ opinion? Explain Justice Stevens’ dissenting opinion. Do you agree? Explain Justice Thomas’ dissenting opinion.

B. How have the precedents of Bethel v. Fraser and Morse v. Frederick narrowed Tinker v. Des Moines? How do the facts of these cases differ? Was the Court’s reasoning in Frederick consistent with Tinker, or do you agree with Justice Thomas that Tinker should be overturned?

Purchase or download your copy today! Interested in bulk purchasing? Email us at [email protected] to discuss pricing.