December 6, 2024

3 min read

Wuhan Virologist Says Lab Has No Close Relatives to COVID Virus

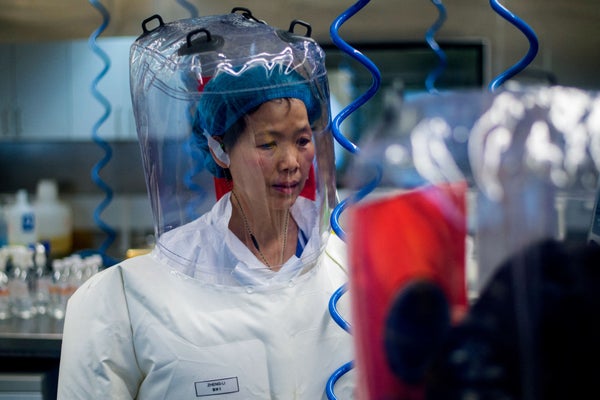

Shi Zhengli, the virologist at the center of COVID lab-leak theory, reveals coronavirus sequences from the Wuhan institute

Chinese virologist Shi Zhengli has presented evidence that her lab has not worked with close relatives of SARS-CoV-2.

Johannes Eisele/AFP via Getty Images

After years of rumours that the virus that causes COVID-19 escaped from a laboratory in China, the virologist at the centre of the claims has presented data on dozens of new coronaviruses collected from bats in southern China. At a conference in Japan this week, Shi Zhengli, a specialist on bat coronaviruses, reported that none of the viruses stored in her freezers are the most recent ancestors of the virus SARS-CoV-2.

Shi was leading coronavirus research at the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV), a high-level biosafety laboratory, when the first cases of COVID-19 were reported in that city. Soon afterwards, theories emerged that the virus had leaked — either by accident or deliberately — from the WIV.

Shi has consistently said that SARS-CoV-2 was never seen or studied in her lab. But some commentators have continued to ask whether one of the many bat coronaviruses her team collected in southern China over decades was closely related to it. Shi promised to sequence the genomes of the coronaviruses and release the data.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The latest analysis, which has not been peer reviewed, includes data from the whole genomes of 56 new betacoronaviruses, the broad group to which SARS-CoV-2 belongs, as well as some partial sequences. All the viruses were collected between 2004 and 2021.

“We didn’t find any new sequences which are more closely related to SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2,” said Shi, in a pre-recorded presentation at the conference, Preparing for the Next Pandemic: Evolution, Pathogenesis and Virology of Coronaviruses, in Awaji, Japan, on 4 December. Earlier this year, Shi moved from the WIV to the Guangzhou Laboratory, a newly established national research institute for infectious diseases.

The results support her assertion that the WIV lab did not have any bat-derived sequences from viruses that were more closely related to SARS-CoV-2 than were any already described in scientific papers, says Jonathan Pekar, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Edinburgh, UK. “This just validates what she was saying: that she did not have anything extremely closely related, as we’ve seen in the years since,” he says.

The closest known viruses to SARS-CoV-2 were found in bats in Laos and Yunnan, southern China — but years, if not decades, have passed since they split from their common ancestor with the virus that causes COVID-19. “She’s basically found a lot of what we expect,” says Leo Poon, a virologist at the University of Hong Kong.

Longtime collaboration

For decades, Shi collaborated with Peter Daszak, president of the EcoHealth Alliance, a New York City-based non-profit organization, to survey bats in southern China for coronaviruses and study their risk to humans. The work was funded by the US National Institutes of Health and the US Agency for International Development, but in May this year, the government suspended federal funding to EcoHealth because it had not provided adequate oversight of research activities at the WIV. Those activities included modifying a coronavirus linked to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), to study the potential origins of this type of virus in bats.

Over the years, the collaboration between Shi and Daszak collected more than 15,000 swabs from bats in the region. The team tested these for coronaviruses, and re-sequenced the genomes of those that tested positive. The collection expands the known diversity of coronaviruses. “She found sequences that can at the very least provide more context to our understanding of coronaviruses,” says Pekar.

In a larger analysis of 233 sequences — including the new sequences and some that had previously been published — Shi and her colleagues identified 7 broad lineages and evidence of viruses extensively swapping chunks of RNA, a process known as recombination. Daszak says the analysis also assesses the risk of these viruses jumping to people and identifies potential drug targets; “information of direct value to public health”.

Daszak says the team has experienced delays in submitting the work for peer review, owing to funding cuts, challenges working across regions and several US government investigations of EcoHealth. However, the researchers plan to submit the analysis to a journal in the next few weeks.

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on December 6, 2024.