Piaget Learning Theory: Stages Of Cognitive Development

by TeachThought Staff

Jean Piaget (1896-1980) was a Swiss psychologist and one of the most influential figures in the field of developmental psychology.

Piaget is best known for his pioneering work on the cognitive development of children. His research revolutionized our understanding of how children learn and grow intellectually. He proposed that children actively construct their knowledge through a series of stages, each characterized by distinct ways of thinking and understanding the world.

His theory, ‘Piaget’s stages of cognitive development,’ has profoundly impacted formal education, emphasizing the importance of tailoring teaching methods to a child’s cognitive developmental stage rather than expecting all children to learn similarly.

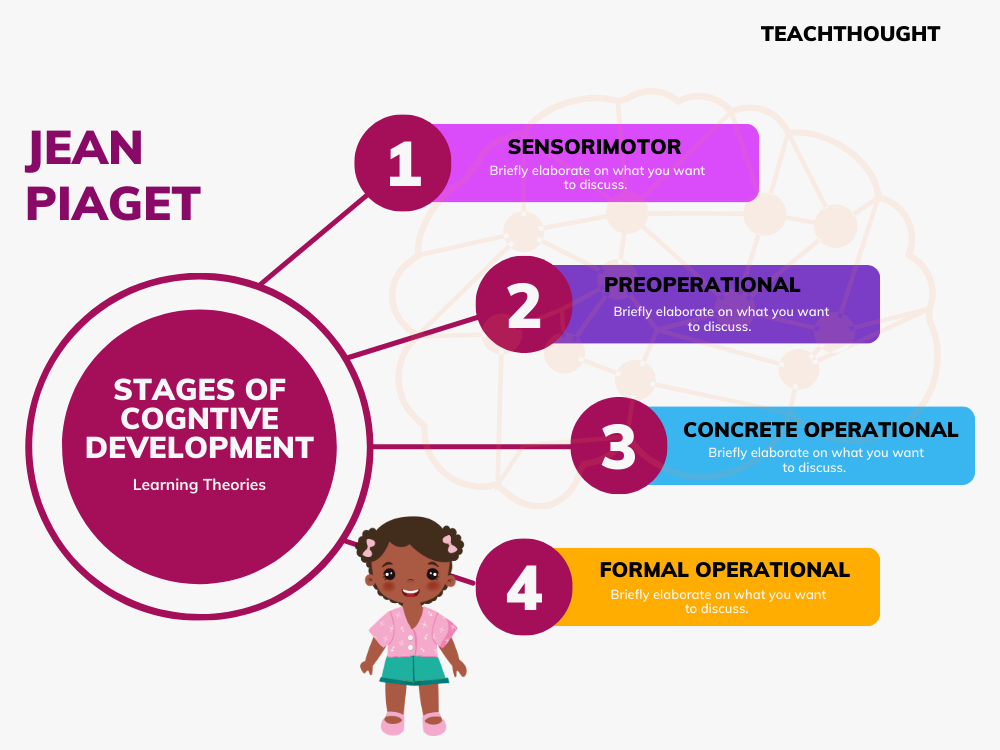

Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development outlines a series of developmental stages that children progress through as they grow and mature. This theory suggests that children actively construct their understanding of the world and distinct cognitive abilities and ways of thinking characterize these stages. The four main stages are the sensorimotor stage (birth to 2 years), the preoperational stage (2 to 7 years), the concrete operational stage (7 to 11 years), and the formal operational stage (11 years and beyond).

A Quick Summary Of Piaget’s Stages Of Cognitive Development

In the sensorimotor stage, infants and toddlers learn about the world through their senses and actions, gradually developing object permanence. The preoperational stage is marked by the emergence of symbolic thought and the use of language, although logical thinking is limited. The concrete operational stage sees children begin to think more logically about concrete events and objects.

Finally, in the formal operational stage, adolescents and adults can think abstractly and hypothetically, allowing for more complex problem-solving and reasoning. Piaget’s theory has influenced teaching methods that align with students’ cognitive development at different ages and stages of intellectual growth.

Piaget’s Four Stages Of Cognitive Development

Piaget’s Stage 1: Sensorimotor

Piaget’s sensorimotor stage is the initial developmental stage, typically occurring from birth to around two years of age, during which infants and toddlers primarily learn about the world through their senses and physical actions.

Key features of this stage include the development of object permanence, the understanding that objects continue to exist even when they are not visible, and the gradual formation of simple mental representations. Initially, infants engage in reflexive behaviors, but as they progress through this stage, they begin to intentionally coordinate their sensory perceptions and motor skills, exploring and manipulating their environment. This stage is marked by significant cognitive growth as children transition from purely instinctual reactions to more purposeful and coordinated interactions with their surroundings.

One example of Piaget’s sensorimotor stage is when a baby plays peek-a-boo with a caregiver. In the early months of life, an infant lacks a sense of object permanence. When an object, like the caregiver’s face, disappears from their view, they may act as if it no longer exists. So, when the caregiver covers their face with their hands during a peek-a-boo game, the baby might respond with surprise or mild distress.

As the baby progresses through the sensorimotor stage, typically around 8 to 12 months of age, they begin to develop object permanence. When the caregiver hides their face, the baby understands that the caregiver’s face still exists, even though it’s temporarily out of sight. The baby may react with anticipation and excitement when the caregiver uncovers their face, demonstrating their evolving ability to form mental representations and grasp the concept of object permanence.

This progression in understanding is a key feature of the sensorimotor stage in Piaget’s theory of cognitive development.

Piaget’s Stage 2: Preoperational

Piaget’s preoperational stage is the second stage of cognitive development, typically occurring from around 2 to 7 years of age, where children begin to develop symbolic thinking and language skills. During this stage, children can represent objects and ideas using words, images, and symbols, enabling them to engage in pretend play and communicate more effectively.

However, their thinking is characterized by egocentrism, where they struggle to consider other people’s perspectives, and they exhibit animistic thinking, attributing human qualities to inanimate objects. They also lack the ability for concrete logic and struggle with tasks that require understanding conservation, such as recognizing that the volume of a liquid remains the same when poured into different containers.

The Preoperational stage represents a significant shift in cognitive development as children transition from basic sensorimotor responses to more advanced symbolic and representational thought.

One example of Piaget’s preoperational stage is a child’s understanding of the concept of ‘conservation.’

Imagine you have two glasses, one tall and narrow and the other short and wide. You pour the same amount of liquid into both glasses to contain the same volume of liquid. A child in the preoperational stage, when asked whether the amount of liquid is the same in both glasses, might say that the taller glass has more liquid because it looks taller. This demonstrates the child’s inability to understand the principle of conservation, which is the idea that even if the appearance of an object changes (in this case, the shape of the glass), the quantity remains the same.

In the preoperational stage, children are often focused on the most prominent perceptual aspects of a situation and struggle with more abstract or logical thinking, making it difficult for them to grasp conservation concepts.

Piaget’s Stage 3: Concrete Operational

Piaget’s Concrete Operational stage is the third stage of cognitive development, typically occurring from around 7 to 11 years of age, where children demonstrate improved logical thinking and problem-solving abilities, particularly in relation to concrete, tangible experiences.

During this stage, they can understand concepts such as conservation (e.g., recognizing that the volume of liquid remains the same when poured into different containers), and reversibility (e.g., understanding that an action can be undone) and can perform basic mental operations like addition and subtraction. They become more capable of considering different perspectives, are less egocentric, and can engage in more structured and organized thought processes, yet they may still struggle with abstract or hypothetical reasoning, which is a skill that emerges in the subsequent formal operational stage.

Imagine two identical containers filled with the same amount of water. You pour the water from one of the containers into a taller, narrower glass and pour the water from the other into a shorter, wider glass. A child in the concrete operational stage would be able to recognize that the two glasses still contain the same amount of water despite their different shapes. Children can understand that the physical appearance of the containers (tall and narrow vs. short and wide) doesn’t change the quantity of the liquid.

This ability to grasp the concept of conservation is a hallmark of concrete operational thinking, as children become more adept at logical thought related to real, concrete situations.

Stage 4: The Formal Operational Stage

Piaget’s Formal Operational stage is the fourth and final stage of cognitive development, typically emerging around 11 years of age and continuing into adulthood. During this stage, individuals gain the capacity for abstract and hypothetical thinking. They can solve complex problems, think critically, and reason about concepts and ideas unrelated to concrete experiences. They can engage in deductive reasoning, considering multiple possibilities and potential outcomes.

This stage allows for advanced cognitive abilities like understanding scientific principles, planning for the future, and contemplating moral and ethical dilemmas. It represents a significant shift from concrete to abstract thinking, enabling individuals to explore and understand the world in a more comprehensive and imaginative way.

An Example Of The Formal Operation Stage

One example of Piaget’s Formal Operational stage involves a teenager’s ability to think abstractly and hypothetically.

Imagine presenting a teenager with a classic moral dilemma, such as the ‘trolley problem.’ In this scenario, they are asked to consider whether it’s morally acceptable to pull a lever to divert a trolley away from a track where it would hit five people, but in doing so, it would then hit one person on another track. A teenager in the formal operational stage can engage in abstract moral reasoning, considering various ethical principles and potential consequences, without relying solely on concrete, personal experiences.

They might ponder utilitarianism, deontology, or other ethical frameworks, and they can think about the hypothetical outcomes of their decisions.

This abstract and hypothetical thinking is a hallmark of the formal operational stage, demonstrating the capacity to reason and reflect on complex, non-concrete issues.

How Teachers Can Use Piaget’s Stages Of Development in The Classroom

1. Individual Differences

Understand that children in a classroom may be at different stages of development. Tailor your teaching to accommodate these differences. Provide a variety of activities and approaches to cater to various cognitive levels.

2. Constructivism

Recognize that Piaget’s theory is rooted in constructivism, meaning children actively build their knowledge through experiences. Encourage hands-on learning and exploration, as this aligns with Piaget’s emphasis on learning through interaction with the environment.

3. Scaffolding

Be prepared to scaffold instruction. Students in the earlier stages (sensorimotor and preoperational) may need more guidance and support. As they progress to concrete and formal operational stages, gradually increase the complexity of tasks and give them more independence.

4. Concrete Examples

Students benefit from concrete examples and real-world applications in the concrete operational stage. Use concrete materials and practical problems to help them grasp abstract concepts.

5. Active Learning

Promote active learning. Encourage students to think critically, solve problems, and make connections. Use open-ended questions and encourage discussions that help students move from concrete thinking to abstract reasoning in the formal operational stage.

6. Developmentally Appropriate Curriculum

Ensure that your curriculum aligns with the students’ cognitive abilities. Introduce abstract concepts progressively and link new learning to previous knowledge.

7. Respect for Differences

Be patient and respectful of individual differences in development. Some students may grasp concepts earlier or later than others, and that’s entirely normal.

8. Assessment

Develop assessment strategies that match the students’ developmental stages. Assess their understanding using methods that are appropriate to their cognitive abilities.

9. Professional Development

Teachers can stay updated on the latest child development and education research by attending professional development workshops and collaborating with colleagues to continually refine their teaching practices.