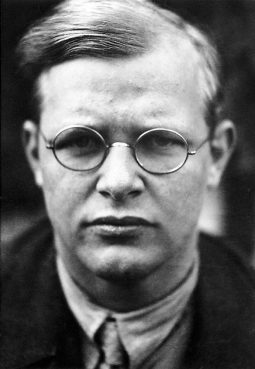

(RNS) — In the decades since he was executed in Germany for crimes of high treason, Dietrich Bonhoeffer has become one of the most celebrated religious thinkers of our time, inspiring many of our era’s most influential leaders, intellectuals and artists, from Desmond Tutu and Vaclav Havel to Jimmy Carter, Angela Merkel and U2’s Bono. He is a model to millions more who confront the blood-stained face of history with courage and conviction.

British journalist Malcolm Muggeridge summed up how this brilliant pastor-turned-conspirator against Hitler became a hero in widely disparate religious traditions: “Some words Gorky used about Tolstoy come into my mind: ‘Look what a wonderful man is living on this earth!’”

But with the adoration of Bonhoeffer’s legacy comes sharp disagreement over its meaning and political uses.

A quick Google search of Bonhoeffer — or better, “Are we living in a Bonhoeffer moment?” — will put the reader directly into the crossfire between liberals and conservatives, each laying claim to the great Christian martyr’s moral inheritance. The relative dearth of explicit political discussion in his writings has made it easy for those with differing theological and ideological stances to cast Bonhoeffer in their own image.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer lived from 1906 to 1945. (Photo courtesy Joshua Zajdman/Random House)

In fact, Bonhoeffer’s political views, as gleaned from his biography, don’t map neatly onto today’s American left-right divides (nor onto the political map of the 1930s America that Bonhoeffer twice visited).

When today’s progressives laud him, they rarely cite his posthumously published book “Ethics” that called abortion “nothing but murder.” Nor do they recall his preference for monarchy over democracy, his dismissal of psychotherapy and psychoanalysis as the mere “gnawing away of otherwise healthy people’s confidence and security” or his sartorial extravagance. His privilege as a golden child of Berlin’s posh Grunewald district, which he wielded freely and without apology, tends to go unremarked among those who prize his “view from below” and solidarity with the poor.

On the religious right, a new generation of activist theocrats has convinced the rank and file that life under any Democratic administration will become a Fourth Reich and have turned Bonhoeffer into a political avatar. Who would not wish that a person we so greatly admire would have seen the world as we do?

Except that MAGA enthusiasts such as author and radio personality Eric Metaxas have transformed Bonhoeffer with little basis in fact. Ignoring biographical features he doesn’t like and inventing new parts he needs, Metaxas has recast Bonhoeffer’s story as a battle cry for conservative Christian activism in every American presidential election since the first Obama administration. He goes to such an extreme as to suggest moral equivalence between the political assassination of an American Democrat with Bonhoeffer’s involvement in a plot to kill Hitler.

Metaxas’ delusionally dangerous portrayal prompted 86 members of the Bonhoeffer family to release a public letter on Oct. 18 condemning the distortions and misuse of “right-wing extremists, xenophobes and religious agitators … whose intentions are diametrically opposed to Bonhoeffer’s thoughts and actions; ranging from Project 2025 — the Heritage Foundation’s proposed program for Trump — to the German right-wing extremist Björn Höcke.”

How should we responsibly position Bonhoeffer within the current American political scene? A good place to start might be to ask how he actually voted.

In the only free election in which he participated, Bonhoeffer supported the Catholic Center Party, which drew its membership from aristocrats, priests, bourgeoisie, peasants, workers. It was the only party that had half a chance of defeating Hitler, Bonhoeffer believed, with its Vatican ties purportedly offering some buffer from full state control. Though Roman Catholic, the Center Party became a reliable inter-confessional partner in the various Weimar coalitions of the 1920s. It supported the separation of church and state and welfare capitalism, views that would not find a welcome reception with the Christian right in the United States.

Bonhoeffer was proven naïve, of course; when the Nazis came to power in 1933, the Center Party signed the Enabling Act, empowering Hitler “to assume dictatorial powers in Germany” and dissolve every party competing with his own.

Further insight into Bonhoeffer’s political leanings comes from his experience in the United States as a young theologian. While studying with Reinhold Niebuhr at Union Theological Seminary in Manhattan in 1930 and 1931, Bonhoeffer encountered the American organizing tradition and its innovations in social ministry. Though initially vexed by American seminarians’ casual disregard for the doctrinal debates of the Protestant Reformation, he was won over by the robust social engagement of Union’s professors, students and clergy.

“Bonhoeffer” film poster. (Image courtesy Angel Studios)

In field trips with classmates, Bonhoeffer met with representatives of the National Women’s Trade Union League, the NAACP and the Workers’ Education Bureau of America. And, as he wrote to his pastoral supervisor in Berlin, “I visited housing settlements, Y.M. home missions, co-operative houses, playgrounds, children’s courts, night schools, socialist schools, asylums, (and) youth organizations.”

It is the signal virtue of the new biopic, “Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Spy, Assassin,” released last month to strong box office numbers, to portray with remarkable ardor his encounters with American religion and society, especially his deep immersion in African American Christianity and culture. Bonhoeffer said he “heard the Gospel preached in the Negro churches,” and it sounded refreshingly different from the somber Lutheranism of the north German plains. He encountered the “Jesus of the disinherited,” to cite the Black Christian mystic and pastor, Howard Thurman.

Bonhoeffer would later say that these spaces of social hope existing in and beyond parish churches’ walls enabled a “turning from the phraseological to the real.” In one largely forgotten episode of his American year, Bonhoeffer took a road trip from New York to Mexico City through the Jim Crow South. He drove through Alabama the same month nine young black men, who had been falsely accused of raping white women, were convicted in a mob atmosphere in successive trials in Scottsboro, Alabama. “Blood laws, mob rule, sterilizations, and land seizures,” he wrote in his notes.

Returning to Berlin in the summer of 1931, Bonhoeffer told his atheist older brother, Karl-Friedrich, that Germany would need an ACLU of its own: The rights of conscientious objectors, protections for resident aliens from deportation and racial disenfranchisement mattered deeply. After denouncing the German church’s support of the Aryan Clause in 1933, Bonhoeffer’s life was set on a collision course with Hitler.

Perhaps what makes it so difficult to understand Bonhoeffer is that we do not often see Christians combine social idealism, pro-life ethics and fervent devotion to Jesus Christ. But these dissidents, dreamers and peacemakers who cut against the grain of the principalities and powers are out there. I am thinking of those Americans who people the faith-based reformist tradition hymned in two recent volumes from the Project on Lived Theology, the research community I am affiliated with at the University of Virginia: ordinary saints such as Ella Baker, Dorothy Day, Cesar Chavez, Mary Paik Lee, Florence Jordan, Sarah Patton Boyle and Ramon Dagoberto Quiñones.

The testimonies of these people are not readily reduced to sound bites, yet this is precisely the form that marks Bonhoeffer’s distinctive witness — a form without any natural partisan home.

Bonhoeffer’s response to our situation would begin with bold, straightforward questions such as those that animate his letters and papers written from a Gestapo prison in the months preceding his death: “Who is Christ for us today?” “Are we still of any use?” “How can Christ become Lord of the religious?” “Why are ‘good people’ often more inclined toward ‘ultimate honesty’ and ‘righteous action’ than church people?” What does God desire but for all humanity to show mercy and act justly?

Bonhoeffer prayed there would arise a generation of “responsible thinking people” with the strength to stand fast, exemplify civil courage and cleave to honesty. He asked whether the “time of words is over,” whether religious language has been so thoroughly profaned that the only way forward is through “prayer and righteous action.”

Bonhoeffer matters because he reminds us that Christian behavior and attitudes are more than calculations for a partisan edge. He understood that a true disciple is “clothed not in the adornments of nationhood and race,” but in the excellences of Christ. Faith ought never divide the self into two halves, he said. “For it is only when one loves life and the earth so much that without them everything seems to be over that one may believe in the resurrection and a new world.”

(Charles Marsh teaches in the religious studies department at the University of Virginia and directs the Project on Lived Theology. He is the author of the award-winning biography “Strange Glory: A Life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)