Organs Age in Waves Accelerating at 50 Years Old

Aging is a complex process that plays out differently across different organs, according to growing evidence

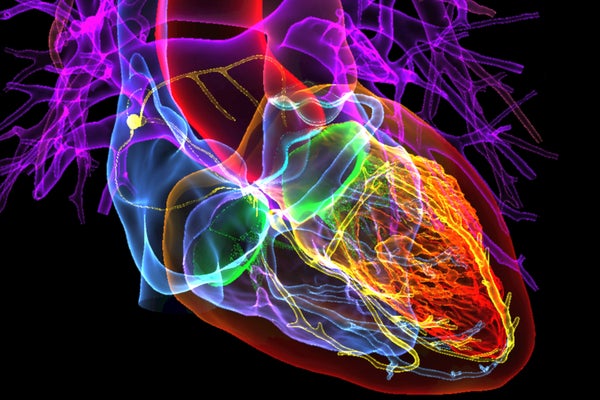

Color enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the human heart, highlighting the cardiac conduction system (yellow).

It is a warning that middle-aged people have long offered the young: ageing is not a smooth process. Now, an exhaustive analysis of how proteins change over time in different organs backs up that idea, finding that people experience an inflection point at around 50 years old, after which ageing seems to accelerate.

The study, published 25 July in Cell, also suggests that some tissues — especially blood vessels — age faster than others, and it identifies molecules that can hasten the march of time.

The findings add to mounting evidence that ageing is not linear, but is instead pockmarked by periods of rapid change. Even so, larger studies are needed before scientists can label the age of 50 as a crisis point, says Maja Olecka, who studies ageing at the Leibniz Institute on Aging — Fritz Lipmann Institute in Jena, Germany, and was not involved in the study.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“There are these waves of age-related changes,” she says. “But it is still difficult to make a general conclusion about the timing of the inflection points.”

Showing their age

Previous work has shown that different organs can age at different rates. To further unpick this, Guanghui Liu, who studies regenerative medicine at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, and his colleagues, collected tissue samples from 76 people of Chinese ancestry aged 14 to 68 who had died from accidental brain injury. The samples came from organs representing eight of the body’s systems, including the cardiovascular, immune and digestive systems.

The researchers then created a compendium of the proteins found in each of the samples. They found age-related increases in the expression of 48 disease-associated proteins, and saw early changes at around age 30 in the adrenal gland, which is responsible for producing various hormones.

This tracks well with previous data, says Michael Snyder, a geneticist at the Stanford University School of Medicine in California. “It fits the idea that your hormonal and metabolic control are a big deal,” he says. “That is where some of the most profound shifts occur as people age.”

Between the ages of 45 and 55 came a turning point marked by large changes in protein levels. The most dramatic shift was found in the aorta, the body’s main artery, which carries oxygenated blood out of the heart. The team tracked down one protein produced in the aorta that, when administered to mice, triggers signs of accelerated ageing. Liu speculates that blood vessels act as a conduit, carrying molecules that promote ageing to remote destinations throughout the body.

The study is an important addition to others that have analysed molecules circulating in the blood, rather than tissue samples taken from individual organs, as a way to monitor age-related changes, says Snyder. “We’re like a car,” he says. “Some parts wear out faster.” Knowing which parts are prone to wear and tear can help researchers to develop ways to intervene to promote healthy ageing, he says.

Halfway to 100

Last year, Snyder and his colleagues found ageing inflection points around the ages of 44 and 60. Other studies have found accelerated ageing at different times, including at around 80 years old, which was beyond the scope of the current study, says Olecka.

Discrepancies with other studies can emerge from their use of different kinds of samples, populations and analytical approaches, says Liu. As data build over time, key molecular pathways involved in ageing will probably converge across studies, he adds.

These data will accumulate rapidly, says Olecka, because researchers are increasingly incorporating detailed time series in their studies, rather than simply comparing ‘young’ with ‘old’. And those results could help researchers to interpret these periods of rapid change. “Currently, we do not understand what triggers this transition point,” she says. “It’s a really intriguing emerging field.”

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on July 25, 2025.